Onur

[CH]

- THE WORK -

Origin

TITLE: origin

Technique: PAINTING

YEAR CREATED: 2021

Location: Rue Jehan Droz

SURFACE AREA: 32 m2

THE WATCHMAKER, NATURE AND THE BORDER

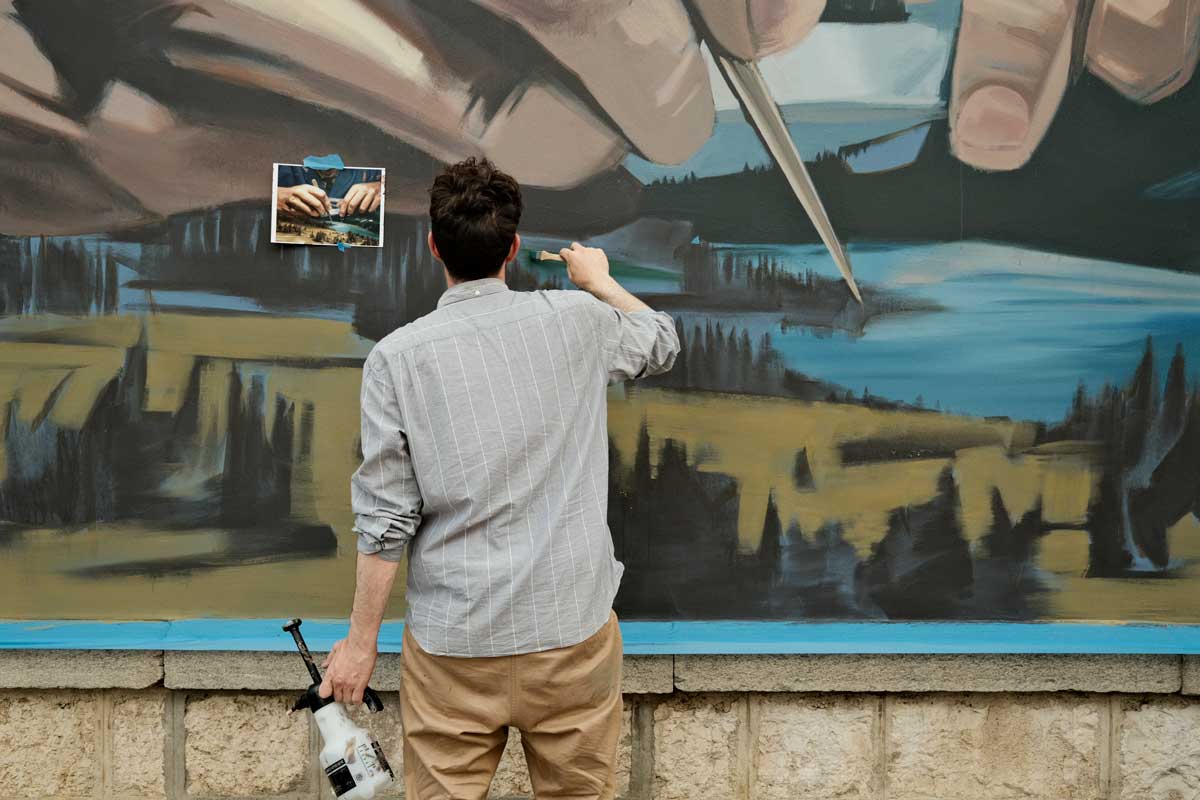

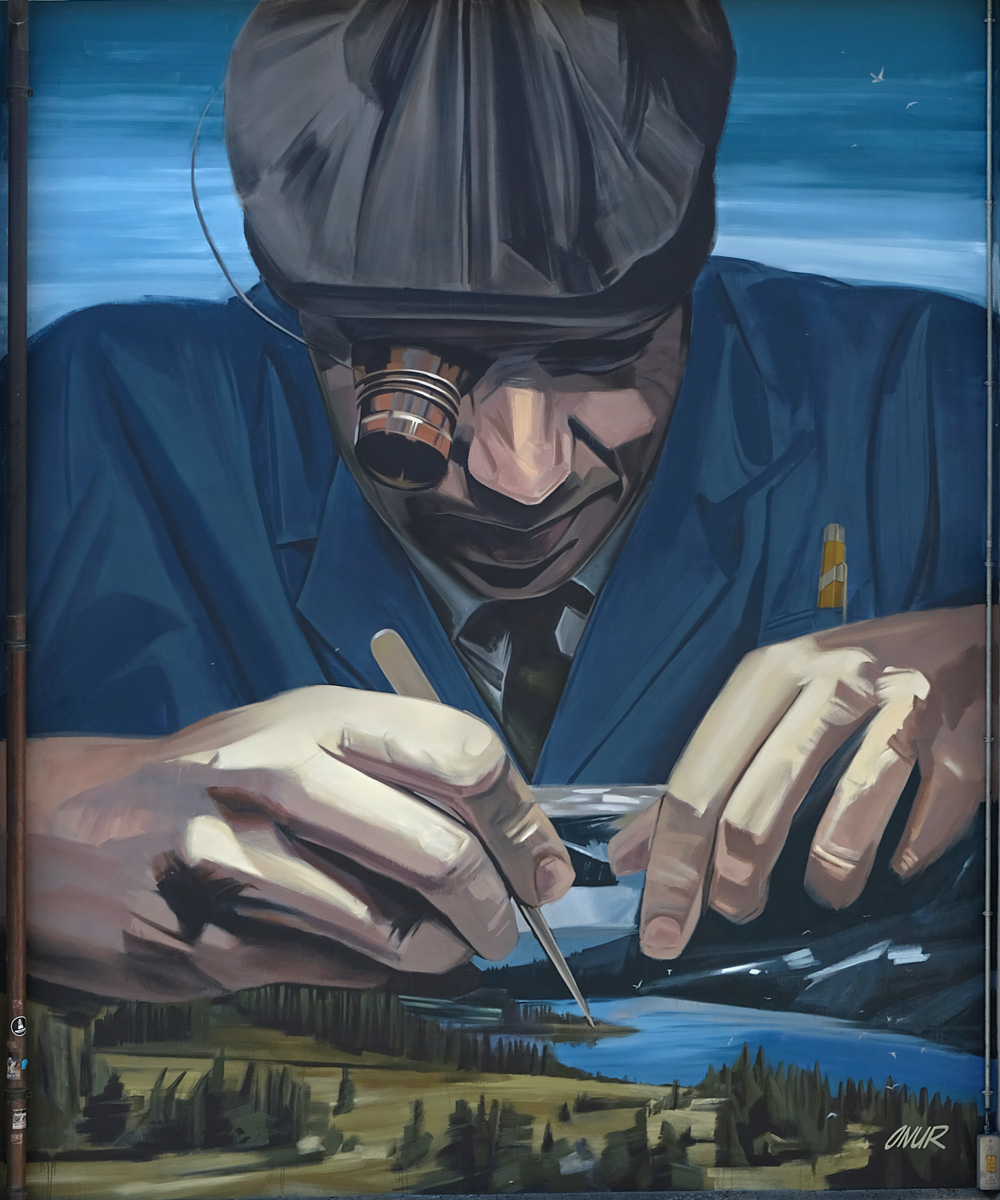

In the foreground, the watchmaker’s hands seem to be coming out of the mural, bathed in the light of an oil lamp. By choosing this composition, Onur is paying homage to the precise movements and manual dexterity of these craftsmen.

Since the mid-20th century, the standard uniform of watchmakers has been a white coat, making them look like doctors. Far removed from that dust-free, clinical environment, Onur preferred to evoke the world of the 19th century watchmaker. Wearing a shirt and tie, topped by a beret, and in an overall that is symbolic of the working class and indeed of the agrarian world, this master watchmaker sees his work bench turn into the typical landscape of the Neuchâtel mountains; in fact, that part of the valley carved out by the Doubs, the 100 km-long stretch of river that marks a natural border between France and Switzerland from Le Locle to Soubey in the canton of Jura.

Here, like anywhere where man flourishes, nature as we see it is no more than the reflection of the human activities that have transformed it. With the help of his tweezers and his eyeglass, commonly known as “micros” (pronounced “mikròs”), Onur’s watchmaker does his utmost to arrange nature down to the tiniest detail, as if it he were dealing with a model. Carefully. A bit like a benevolent god. Using this metaphor, Onur is expressing the idea that the craftsman, and by extension humanity in general, should give nature the same attention, the same care and the same love that we give our worldly creations.

THE HERITAGE OF THE HUGUENOTS

LE LOCLE AND "ÉTABLISSAGE"

Rue Jehan Droz

THE MYTH OF THE SELF-TAUGHT WATCHMAKER

Daniel JeanRichard (1665-1741) was born in La Sagne, a village near Le Locle. According to an account published in 1766 in tourist material, when he was 15 he managed to repair a horse dealer’s broken watch, a watch that came from England. A year later, after copying the mechanism and completely self-taught, he completed a pocket watch, the first ever made in the Neuchâtel mountains.

To this day, there is no documentary evidence about Daniel JeanRichard’s career. He was an apprentice blacksmith in La Sagne just outside Le Locle before becoming a watchmaker. Back then, the Neuchâtel mountains were already home to a hundred or so watchmakers, but even so, JeanRichard is considered the father of watchmaking in the canton of Neuchâtel while his predecessors have largely been forgotten. At the end of the 17th century, the watchmaking trade was strictly regulated. To be a watchmaker, you had to sign a notarised contract and complete a five-year apprenticeship alongside a master. Then, to reach the rank of master watchmaker and teach others, you had to be admitted to the guild and show yourself worthy of its trust. The fact that Daniel JeanRichard trained numerous apprentices suggests that he met all these requirements.

For a country, a region or a town, founding myths reinforce a sense of identity for the people who live there and increase the appeal of a place by communicating attractive and colourful values. The story that depicts Daniel JeanRichard as a genius is doubtless in the same vein as the myth of the peasant watchmaker that glorifies the ingenuity and entrepreneurial spirit of the people of the Neuchâtel mountains.

- THE ARTIST -

Onur Dinc

Onur Dinc was born in Zurchwil in the canton of Solothurn in 1979. His passion for figurative painting was initially ignited by his older sister, Emel, who despite her artistic potential put away her brushes for good when she reached adulthood.

While a career in art can be considered financially and existentially risky in middle-class families, this is even truer for people from more modest backgrounds. So when Onur decided to become a painter after finishing school, it was not a given that his parents would be supportive. His father’s experience as a Turkish immigrant and life in a factory meant that he knew very little about art and frowned on his son’s artistic ambitions.

Ignoring his parents’ concerns, Onur Dinc completed his apprenticeship as a painter and then studied set design for four years, painting theatre sets in Solothurn. He then trained for three years as a graphic designer at the FAVO advertising agency in Basel and then for just a year in Bern. At the age of 27, Onur started exhibiting his work in Swiss cities and in Germany. In 2007, he worked again as a theatre set painter in Lucerne before deciding the following year to devote himself entirely to his art.

He discovered the world of street art in 2008. His encounter with Remo Lienhard – a brilliant painter who goes by the name of WES-21 – and Pascal Flühmann, alias KKADE (founder of the Swiss collective “Schwarzmaler” and a member of the famous Californian collective “The Seventh Letter”) triggered his desire to put his art in public spaces. A great artistic complicity quickly developed between the protagonists and led to several collaborations, particularly between Onur and WES-21. The pair became famous creating monumental murals in Basel (CH), Paris (FR), Berlin (DE), Reykjavík (IS), Aalborg (DK), Budapest (HU), Gemona del Friuli (I) and Lagos (PT) and in major US cities such as Miami, Rochester, Richmond and New York… The list of murals made by Onur, collectively or on his own, is still growing.

When he is not perched in a basket or on scaffolding, Onur divides his time between Solothurn and Berlin. When he leaves his studio, it is generally to paint large-scale areas. His artistic approach is poles apart from that of a self-taught graffiti artist. A neo-muralist influenced by photorealism, he works entirely legally in public spaces. In this sense, his work can be described more as urban art than street art, the latter being created as if by a vandal. Today, Onur makes a comfortable living from painting. His work has featured in video clips by the famous German rapper Kool Savas. Unwilling to letting his art serve commercial organisations, he has nevertheless worked on behalf of the carmaker Volvo as part of its global advertising campaign, and for the TV station Canal+. While his main source of income comes from selling canvases and prints, he loves working in the street because the public space is good for spontaneous exchanges with the public, more so than in galleries or museums. His favourite tools are brushes and rollers. His pictorial touch, thanks to gestures that are both precise and free, becomes less obvious as you move further away from the works being viewed. At a distance, his paintings appear less gestural and (even) more realistic. That is when we realise the artist’s precision with each brushstroke. Onur occasionally includes luminescent paint in his murals to illuminate them at night.

Considering that art holds up a mirror to society, Onur believes that the role of artists is to comment on society and raise awareness. His interest in figuration flows from this desire to convey powerful messages by means of philosophically committed and often metaphorical pictorial representations. The damage being inflicted by man on nature, excessive consumerism, contemporary neuroses, everyday stupidity and animal suffering are all issues that inspire Onur.

For his artist name, Onur Dinc has simply chosen his first name, dropping his surname. Commonplace in Turkey and meaning “honour”, “pride” and “dignity”, it is a first name predestined for this virtuoso who is one of the highest profile Swiss street artists with a growing presence. Looking back, Onur is pleased that he was able to convince his parents that this was the right approach for him, doing justice to his first name.

To print the content of the page, please click on the printer icon.

- The exo -

on the web

Thank you for following and supporting the exomusée on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube!