Levalet

[FR]

- THE WORK -

RUN FOR YOUR LIFE

Title: Sauve qui peut [RUN FOR YOUR LIFE]

Technique: PAINTING (ON WOOD)

YEAR CREATED: 2019

Location: Col 27

SURFACE AREA: 18 m2

Explanations and analyses of the works are provided during guided tours. >>> link to the registration form

Why are these workers abandoning their work? Are they on strike? Is it a mutiny, some kind of retreat due to a relocation? The consequences of an industrial revolution? Is it a class struggle? These are the questions the artist raises while allowing everyone the opportunity to come up with their own answer. It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about workers today or from the past because Levalet’s message is universal and timeless: production methods change over time and expertise is lost.

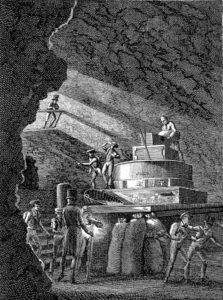

Using the outlines of three windows that have been bricked up for years, Levalet’s installation shines a light on the history of the underground mills and pays homage to the men and women who turned grain into flour, tree trunks into beams and rapeseed into oil in gloomy, damp and cold conditions.

Levalet cleverly uses the building’s structure to define three narrative spaces, a little like an open (two-dimensional) altarpiece.

On the left, taking his courage in both hands, a worker is running away from the building.

In the central cartouche, a fellow worker sitting with his feet dangling in the air gauges his height from the ground and assesses the probability of breaking his neck if he jumps. Standing alongside him, a more timid companion seems torn between wanting to follow his friends and giving in to the temptation to return to work.

In the third cartouche, clinging to the stone ledge, the most fearful of the group is afraid to let go, as if suddenly realising that giving up his source of income would be a leap into the unknown. A desire for more freedom? Perhaps he’s afraid of not having a decent standard of living again.

This work of art speaks of surrender and social collapse. It isn’t about workers mounting the barricades. They’re disillusioned and weary, simply leaving it all behind with no shouting, no jostling, no gesture of support. They make you think of convicts who, having sawn through the bars of their windows, belatedly realise that the prison wall is far too high for them to be able to escape.

The silhouettes of the “deserters” linger in the hollows of the walls of a factory that is now at a standstill. They are like die casts, engravings made with acidic sweat created by repetitive gestures carried out over the years. These impressions suggest that the workers end up in moulds, with the empty existential sarcophagi resembling die casts ready to welcome new workers.

Using the outlines of three windows that have been bricked up for years, Levalet’s installation shines a light on the history of the underground mills and pays homage to the men and women who turned grain into flour, tree trunks into beams and rapeseed into oil in gloomy, damp and cold conditions.

Levalet cleverly uses the building’s structure to define three narrative spaces, a little like an open (two-dimensional) altarpiece.

On the left, taking his courage in both hands, a worker is running away from the building.

In the central cartouche, a fellow worker sitting with his feet dangling in the air gauges his height from the ground and assesses the probability of breaking his neck if he jumps. Standing alongside him, a more timid companion seems torn between wanting to follow his friends and giving in to the temptation to return to work.

In the third cartouche, clinging to the stone ledge, the most fearful of the group is afraid to let go, as if suddenly realising that giving up his source of income would be a leap into the unknown. A desire for more freedom? Perhaps he’s afraid of not having a decent standard of living again.

This work of art speaks of surrender and social collapse. It isn’t about workers mounting the barricades. They’re disillusioned and weary, simply leaving it all behind with no shouting, no jostling, no gesture of support. They make you think of convicts who, having sawn through the bars of their windows, belatedly realise that the prison wall is far too high for them to be able to escape.

The silhouettes of the “deserters” linger in the hollows of the walls of a factory that is now at a standstill. They are like die casts, engravings made with acidic sweat created by repetitive gestures carried out over the years. These impressions suggest that the workers end up in moulds, with the empty existential sarcophagi resembling die casts ready to welcome new workers.

© exomusée – January 2022 – Redaction: François Balmer – Translation: Proverb, Heiler & Co

Col 27

HISTORY OF THE UNDERGROUND MILLS OF COL-DES-ROCHES

To the west of the valley of Le Locle, the waters of the Bied river surge into the sink hole of the Col-des-Roches, forming an underground waterfall several metres high.

In 1652, three millers – Daniel Renaud, Isaac Vuagneux and Balthazard Calame – decided to make use of this cavity and installed two cogwheels to drive a mill and a grinder. Their ingenious use of the site soon awakened the greed of a powerful figure, Jonas Sandoz. Thanks to his influence with the cantonal authorities, he acquired the rights to the millers’ facilities. The latter were paid off and forced to pack up and leave.

Jonas Sandoz was ambitious and turned the cave into a proper factory consisting of five hydraulic wheels supplying enough kinetic energy to operate the mills, a sawmill, a grinder and an oil mill. Tunnels and staircases provided access to the machinery for maintenance. In 1690, Sandoz went bankrupt and had to sell his business.

In the 18th century, the import of flour – prohibited, but tolerated – contributed to a fall in the number of grain mills in the principality. The enterprise at Col-des-Roches changed hands half a dozen times. Successive owners constantly simplified the hydraulic mechanism to reduce maintenance costs. In 1780, the site comprised just three wheels and three working mills.

In 1844, a baker from Le Locle, Jean-Georges Eberlé, bought the site and erected a huge building that housed the mills, a grain cleaning facility, a sifting area and sack hoists. The industrial era was in full swing. One of the hydraulic wheels was replaced by a turbine. Thanks to a fifty-metre drive shaft, the last functioning wheel powered the sawmill machines, which were now located outside the cave at ground level.

In 1884, Eberlé’s heirs sold the mills to Le Locle council. The town planned to drain the boggy valley by changing the watercourse.

In 1898, the mills were turned into an abattoir.

At the start of the 20th century, the site was equipped with new buildings and the very latest facilities. For decades, its owners used the cave as a dumping ground for meat waste and wastewater and in 1966 the heavily polluted sinkhole was blocked up.

From 1973 to 1988, thanks to hard, unpaid work by amateur history lovers and cavers, the underground mills of Col-des-Roches were returned to the public. The site immediately attracted interest.

It was only in 2001, however, that a permanent exhibition about the history of the site and region was staged and a museum opened.

In 2007, the old mills were brought back to life thanks to the installation of a new hydraulic system. The courtyard and old sawmill were improved in 2018.

Temporary exhibitions and other events are regularly held on the site. This museum is unique in Europe and is one of the region’s major tourist attractions.

In 1652, three millers – Daniel Renaud, Isaac Vuagneux and Balthazard Calame – decided to make use of this cavity and installed two cogwheels to drive a mill and a grinder. Their ingenious use of the site soon awakened the greed of a powerful figure, Jonas Sandoz. Thanks to his influence with the cantonal authorities, he acquired the rights to the millers’ facilities. The latter were paid off and forced to pack up and leave.

Jonas Sandoz was ambitious and turned the cave into a proper factory consisting of five hydraulic wheels supplying enough kinetic energy to operate the mills, a sawmill, a grinder and an oil mill. Tunnels and staircases provided access to the machinery for maintenance. In 1690, Sandoz went bankrupt and had to sell his business.

In the 18th century, the import of flour – prohibited, but tolerated – contributed to a fall in the number of grain mills in the principality. The enterprise at Col-des-Roches changed hands half a dozen times. Successive owners constantly simplified the hydraulic mechanism to reduce maintenance costs. In 1780, the site comprised just three wheels and three working mills.

In 1844, a baker from Le Locle, Jean-Georges Eberlé, bought the site and erected a huge building that housed the mills, a grain cleaning facility, a sifting area and sack hoists. The industrial era was in full swing. One of the hydraulic wheels was replaced by a turbine. Thanks to a fifty-metre drive shaft, the last functioning wheel powered the sawmill machines, which were now located outside the cave at ground level.

In 1884, Eberlé’s heirs sold the mills to Le Locle council. The town planned to drain the boggy valley by changing the watercourse.

In 1898, the mills were turned into an abattoir.

At the start of the 20th century, the site was equipped with new buildings and the very latest facilities. For decades, its owners used the cave as a dumping ground for meat waste and wastewater and in 1966 the heavily polluted sinkhole was blocked up.

From 1973 to 1988, thanks to hard, unpaid work by amateur history lovers and cavers, the underground mills of Col-des-Roches were returned to the public. The site immediately attracted interest.

It was only in 2001, however, that a permanent exhibition about the history of the site and region was staged and a museum opened.

In 2007, the old mills were brought back to life thanks to the installation of a new hydraulic system. The courtyard and old sawmill were improved in 2018.

Temporary exhibitions and other events are regularly held on the site. This museum is unique in Europe and is one of the region’s major tourist attractions.

© exomusée – January 2022 – Redaction: François Balmer – Translation: Proverb, Heiler & Co

- THE ARTIST -

Levalet

Charles Leval, known as Levalet, was born in Epinal in 1988 but grew up in Guadeloupe where he came into contact with urban culture and then plastic arts, before returning to France to study visual art in Strasbourg. His work, at the time focused more on video, was inspired by theatre. After qualifying as a teacher in 2012, his work began to take over the streets of Paris and elsewhere. He has exhibited in galleries and participated in international events since 2013. Levalet’s work primarily involves drawings and installations. He presents characters drawn in the public space in Indian ink in a visual and semantic dialogue with their environment. The characters interact with the architecture and are deployed in situations that often border on the absurd.

© exomusée – January 2022 – Redaction: François Balmer – Translation: Proverb, Heiler & Co

To print the content of the page, please click on the printer icon.

- The exo -

on the web

Thank you for following and supporting the exomusée on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube!